Thelonious Monk

Kevin Le Gendre

Monk remains one of the central pillars of the modern jazz era, a man who actually created a unique, idiosyncratic language that often stood apart from any particular genre

His extraordinary name – Thelonious Sphere Monk – sits well with an extraordinary musical personality and an extraordinary life.

Indeed there is a danger of what happened offstage in the pianist’s existence – the insularity and long periods spent in silence; shocking brutality at the hands of the police; denial of professional opportunities on the basis of trumped up drugs charges; lengthy struggles with mental health that have led to speculation of a bi-polar disorder – may well eclipse his artistic legacy.

Yet Monk remains one of the central pillars of the modern jazz era, a man who, although dubbed ‘the high priest of bop’, actually created a unique, idiosyncratic language that often stood apart from that particular sub-genre. Monk’s preferred tempos were mostly more leisurely than the lightning strikes of Bird et al and his improvisations provocatively spaced, the rhythm hard-hitting and harmony often on the edge of ‘proper.’

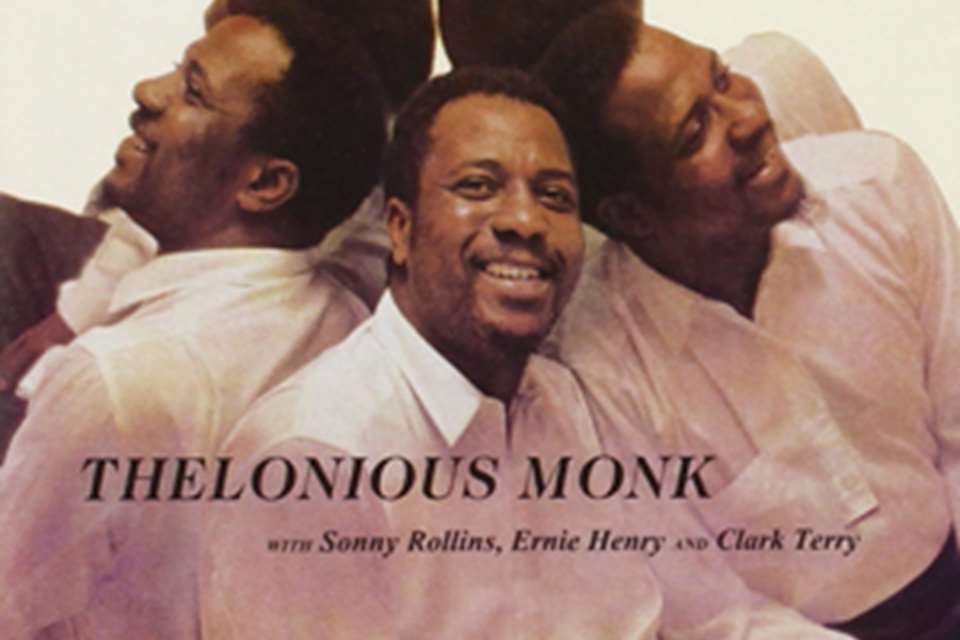

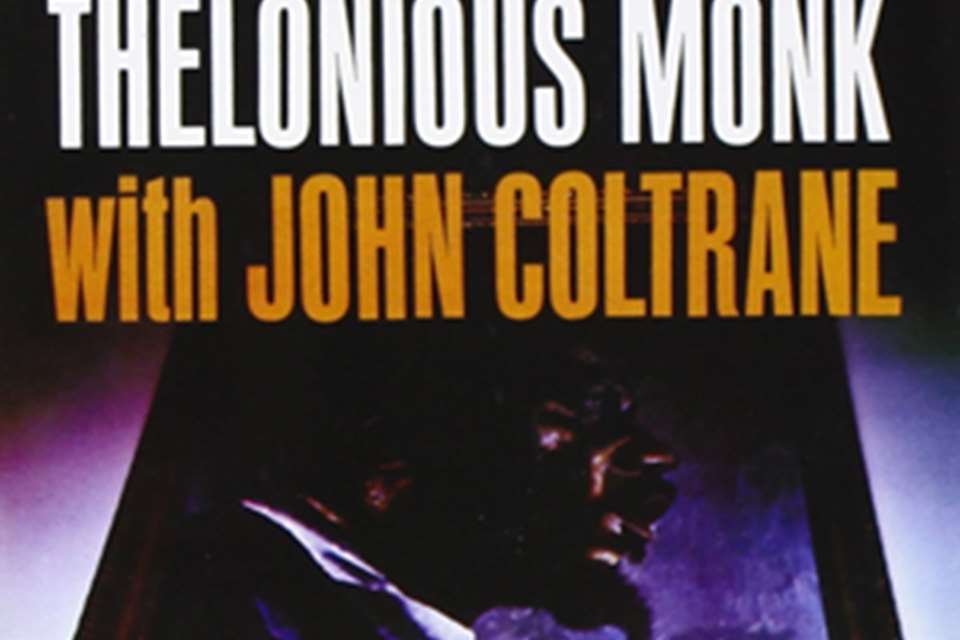

Born in North Carolina in 1917 he grew up in New York, played organ in church, toured with a gospel group in the ‘30s and landed a highly significant gig with Kenny Clarke at Minton’s playhouse in the early ‘40s, where after hours sessions would lead to the birth of what became known as bebop. Although Monk was a member of a big band led by one of the movement’s spearheads, Dizzy Gillespie, he excelled throughout the ‘50s and ‘60s at the helm of his own groups, from trio to quartet to orchestra.

The body of work he created in those decades is outstanding, and albums such as Misterioso, Brilliant Corners and At Town Hall are seminal entries in the canon of 20th century music, jazz or otherwise.

Monk’s singular, off-to-the-side melodies – whimsical but logical, deeply engaging amid the harshness of some of the chordal frameworks – are unforgettable. Yet part of the genius is also in the enormously physical approach to the piano – spreading out the hands to the full while attacking the keyboard vigorously and syncopating sometimes so heavily as to make notes jolt and snap to attention, as is the case on the wonderfully jumpy, Latin-tinged ‘Bye Ya.’

Interestingly, Monk had a passion for both the pioneers of black music as well as the key architects of the Great American songbook, and it is important to hear him perform an Ellington, Gershwin or Van Heusen staple because that reminds us of how great an understanding he had of their lyricism and romanticism all the while imbuing the source material with his own character.

While his death at the age of 65 was untimely his spirit galvanized subsequent generations of players and is heard in anybody from Randy Weston to Cecil Taylor to one of today’s cutting edge players, Jason Moran. The latter has drawn particularly attention to the directness and clarity of Monk’s work, which can yield as much excitement from a 12 bar blues as it can a show tune or one chord riff. Moran has called Monk at his most hypnotic an exponent of ‘genius house music’, apt for dancers of all persuasions.