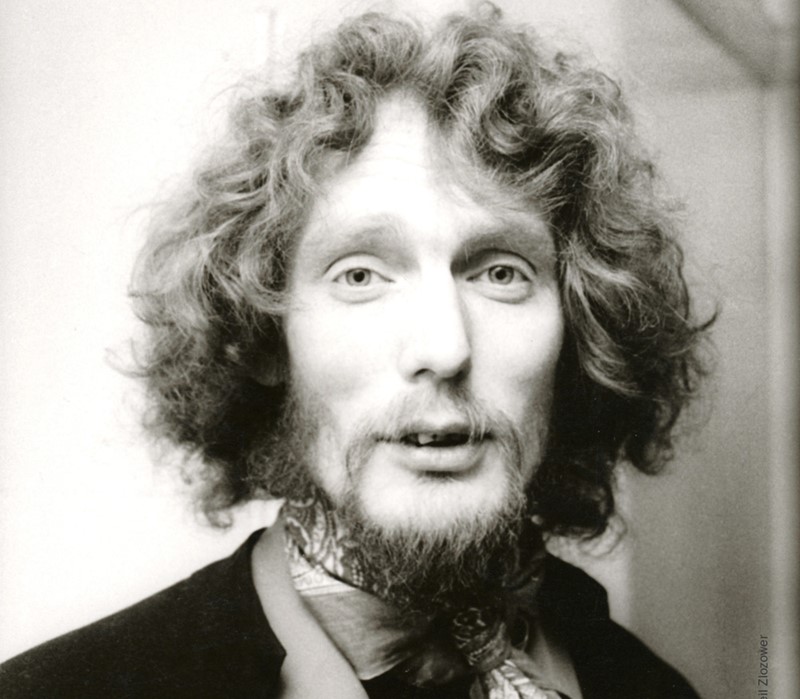

Ginger Baker – 19/8/1939 - 6/10/2019

Jon Newey

Monday, October 7, 2019

One of the all-time giants of the jazz, rock and world music drumming world, Peter ‘Ginger’ Baker died on Sunday 6 October, aged 80, following a period in hospital intensive care.

Baker was a true original, a ferocious force both behind the kit and often in his peripatetic social life, where his unpredictable behavior was captured in the award-winning documentary film, Beware of Mr Baker in 2012. Yet his larger-than-life exploits, across a brace of continents, sometimes overshadowed a truly singular and innovative player, who grew from humble beginnings in wartime Lewisham to become the world’s most talked about drummer by the late 1960s. He was inspired to take up drumming by Max Roach’s performance on the album Quintet of the Year, alongside Parker, Gillespie, Bud Powell and Mingus, an LP that, in his autobiography, Hellraiser, he claimed to have pinched from a record store in Eltham in order to gain respect from a gang he wanted to join. He began playing aged 15 on a starter kit of bits and pieces and soon progressed to a trad jazz band, the Storyville Jazzmen, before being recruited into Terry Lightfoot’s Jazzmen, where, inspired by Big Sid Catlett, he started experimenting with loud off-beat bass drum hits, much to Lightfoot’s annoyance.

Various jazz deps and theatre work followed in which Baker grasped the elements of reading and arrangements, together with a growing appetite for pep pills and ultimately heroin: habits that drew him into the wilder side of Soho life and, not unsurprisingly, Phil Seamen’s circle, a hugely talented but somewhat wayward drummer that Baker and many others idolised. Gigs with the Johnny Burch Band at the Flamingo and Ronnie Scott’s followed where his reputation as an increasingly formidable player led to him to be considered for the Johnny Dankworth Band, but was eventually denied due to drug use. He replaced Charlie Watts in Alexis Korner’s band where he first met bassist Jack Bruce and organist/saxophonist Graham Bond. They all subsequently quit Korner to form the Graham Bond Organisation with saxophonist Dick Heckstall-Smith. This not only became one of the wildest jazz/R&B bands of the mid-1960s, but also infamous for booze and drug use and, in Bond’s case, the occult. Here the remarkable empathy and power, not to mention argumentative qualities, of the Baker-Bruce rhythm section were forged as the drummer soaked up the influences of Art Blakey and Elvin Jones and developed a deep love of African music and drum patterns, a passion that dominated much of his later life.

The UK in the mid-1960s was a white hot crucible of pop/rock/blues experimentalism where the advent of The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, beat and R&B explosion dominated the western world’s youth while pushing jazz temporarily into the shadows. Baker’s next move was to form Cream with Bruce and rising blues/rock guitar maestro Eric Clapton, who rapidly constructed a formidable power trio with improvisatory powers previously unheard in rock music. A group that Bruce said was really “the Ornette Coleman Trio except Eric didn’t realise he was Ornette”. This was Baker’s big moment, switching to a massive, twin Ludwig bass drum set up, festooned with a forest of Zildjian cymbals, his propulsive polyrhythmic drive, rumbling double-bass drum attack and stop-time triplet accents took the world by storm. He quickly became a drum hero, pushed kit sales into the stratosphere and made Ludwig a fortune as he and Bruce’s contrapuntal bass drive pushed Clapton to extraordinary guitar peaks, as exemplified on the huge selling Wheels Of Fire live album. They conquered America and, along with the Jimi Hendrix Experience, brought jazz improvisation to the expanding underground blues-rock scene that became the prime influence among groups over the next five years leading to Led Zeppelin, the legions of heavy metal groups and the birth of jazz-rock.

Cream was literally too hot, in both playing and personalities, to last. Baker followed Clapton into the short-lived but somewhat underrated Blind Faith, before forming his adventurous large ensemble Air Force, featuring jazz names such as Harold McNair and Phil Seamen alongside Steve Winwood and Nigerian Remi Kabaka on congas. Here he merged jazz and rock with African rhythms in a brave but sprawling project that led Baker further towards his love of African music, friendship with Fela Kuti and a move to Lagos, where he opened a recording studio and furthered his passion for horse riding and polo.

Numerous short-lived bands followed, including a spell in Hawkwind, but as Baker’s earnings from Cream diminished tough times followed, not helped by an increasingly chaotic lifestyle, before bassist and producer Bill Laswell brought him to New York in the mid-1980s to record one of John Lydon’s PiL albums. He finally quit his heroin habit in the 1980s and recorded fusion albums with Laswell and violinist L Shankar. He also returned to jazz with the Ginger Baker Trio, featuring Bill Frisell and Charlie Haden, before moving to Colorado and running a ranch.

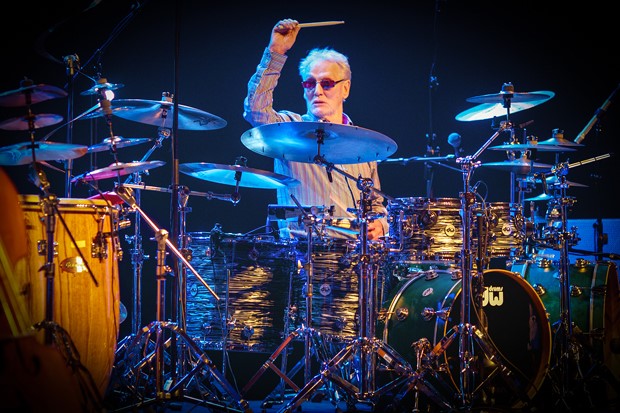

Another short-lived power trio with Jack Bruce and guitarist Gary Moore followed before he moved back to Africa to run a farm in Natal. Then, as money worries became more severe, news that Cream would be getting back together in 2005 came as a musical and financial blessing. The reunion was dynamite with extraordinary concerts at The Royal Albert Hall that went a long way to recapturing the old magic, but was soon abandoned due to the never-ending arguments with Bruce.

He returned to the UK where ill-health dogged him, but in recent years he toured a likeable quartet, Jazz Confusion, with Pee Wee Ellis, Alec Dankworth, Michael Mondesir and Abass Dodoo. They released an album Why?, in 2014 and played Ronnie Scott’s, as well as the jazz festival circuit where the old magic, and the belligerence, would erupt in explosive fills and temper-strewn exclamations, typified by a wonderful, wayward set at Love Supreme Jazz Festival in 2015. A drumming colossus, and unruly, larger than life character the likes of which we’ll sadly rarely see again. Goodnight, Ginge.

– Main photo by Alexis Maryon