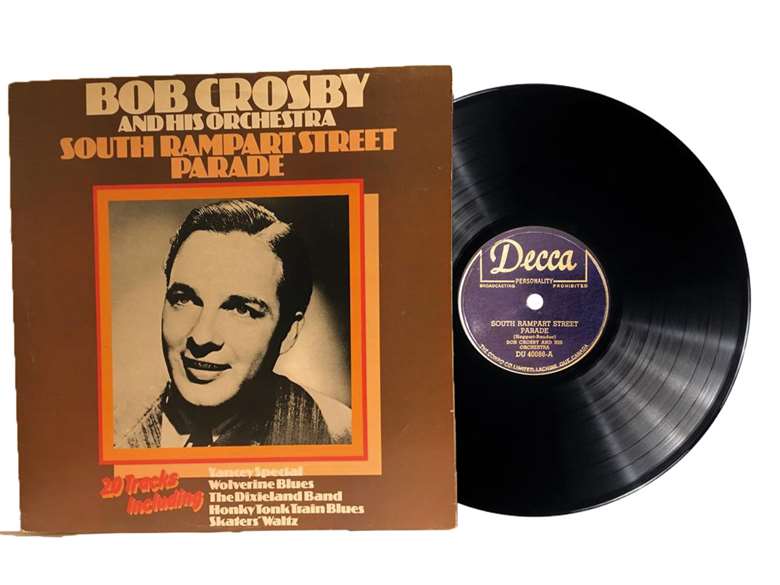

Across the tracks: Bob Crosby’s ‘South Rampart Street Parade’

Brian Priestley

Friday, August 16, 2019

Brian Priestley delves between the notes of Bob Crosby’s ‘South Rampart Street Parade’ (1937)

Even if you don’t accept the proposition that there’s been less jazz innovation in the last 50 years than between 1919 and 1969, you have to agree that our view of the earlier period is becoming more and more streamlined (read: superficial). The New Orleans period is reduced to Louis Armstrong and a fictionalised Buddy Bolden; swing is just Benny Goodman and, if you’re lucky, Count Basie; bebop is Parker and Gillespie; pre-bop saxophone is Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young; Duke Ellington is “beyond category” and so now is Monk. All the rest is “derivative” and therefore not worth the time of day. Except that this leaves out an awful lot of enjoyment and elucidation.

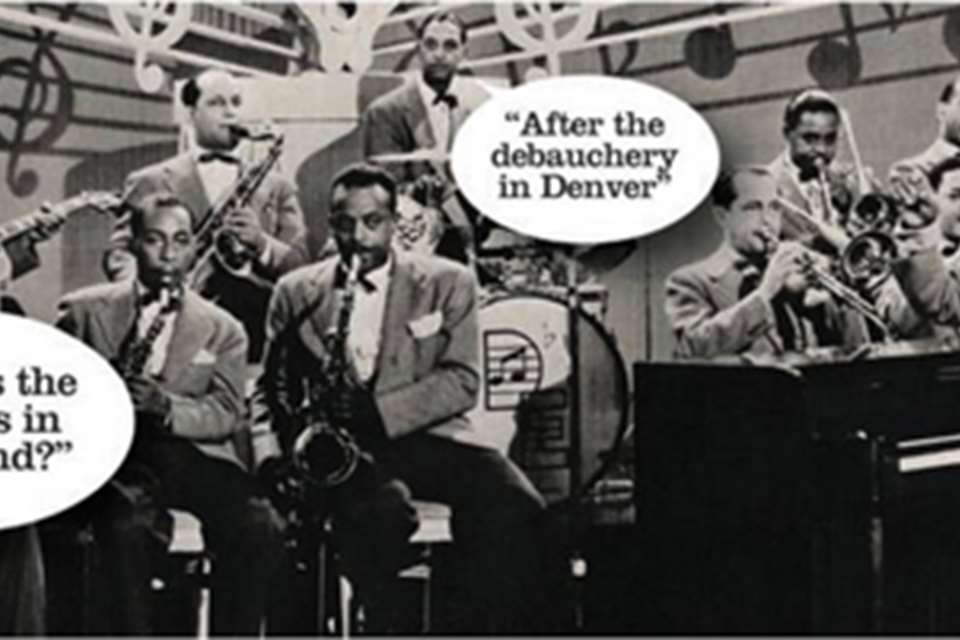

You can read whole books about jazz – even about the swing era – without coming across the name of Bob Crosby, and yet his band had an interesting history and a couple of significant achievements. The nucleus of its membership previously worked for Ben Pollack and, when they walked out on Pollack in 1934, they decided to form a new co-operative outfit and chose Bing Crosby’s younger brother, vocalist Bob, as their frontman. Though at least two-thirds of their recorded singles were vocals (same with contemporary Goodman or Tommy Dorsey, despite retrospective re-evaluations), it’s the instrumentals that cemented their reputation, such as the innovative novelty ‘The Big Noise From Winnetka’ consisting of just drums, bass and whistling by Ray Bauduc and Bob Haggart.

However, even assiduous commentators on the earlier history seem to have assumed that ‘South Rampart Street Parade’ was so well-known and popular that it could be taken for granted and further description was unnecessary. The few interviews with its participants gave little specific information, with the blessed exception of John Chilton who spoke to its co-composers Bauduc and Haggart for his book on the band (Stomp Off, Let’s Go!). According to Chilton, drummer Bauduc hummed the basic tune to Haggart who scribbled it down on a hotel tablecloth, which he then had to steal in order to create an arrangement.

Rampart is, of course, a street in New Orleans and the finished version of this ragtime march is suitably evocative of a location and a musical style, despite being scored for a 13-piece band. The way its themes and their orchestration are mobilised is quite subtle, though that’s hardly the word for the ebullient rendition. For descriptive purposes – unlike the use of cue letters for short sections in a continuously repeated structure – this has several different themes, as in many ragtime or march-influenced pieces. The overall shape of ‘Rampart Street’ is: Intro (8 bars), A (16), B (16), C (32), D (16), C1 (32), C2 (32), C3 (32) and E (16).

The intro is a simple heads-up from drums and unison brass before the rhythm-section enters for the A theme (0’08”), which elaborates the intro with the brass backed by saxes and an improvised clarinet. From 0’26”, a similar feel inhabits B but with written call-and-response between brass and saxes, which leads to a change of key and texture at 0’41” as C is played by a harmonised three-piece frontline led by trumpeter Yank Lawson. The chord-sequences hereto have been very simple (think things like ‘Tiger Rag’), but the C theme borrows from ‘Ol’ Miss Rag’ with its distinctive drop-down at the three-quarter mark – similar to ‘The Preacher’ for a later generation.

At 1’15” the minor-key bridge passage D (reminiscent of ‘High Society March’) soon brings back the original key for C1 (1’33”), the only fully improvised solo with the low-register clarinet of Eddie Miller and just the rhythm-section. This builds to a looser version of the theme on C2 (2’05”) with Lawson embellishing plus roving clarinet and written saxophone backing and, as the temperature rises, the tightly-voiced five-piece brass begin the “shout chorus” (C3, 2’38”). And it is a shout, featuring frequent blue-notes and punchy “modern” phrasing, with Haggart now romping in 4/4 (nearly everything before had a two-beat feel). Behind this, at 2’56” the saxes add back the A theme and, after increased activity in the brass (3’04”), the unexpected coda/extension F is preceded by an electrifying split-second silence (3’11”) where, by prior agreement, no one makes a sound on a single downbeat.

Particularly satisfying and revealing is the fact that the ensemble accents following this silence equate to what we now know as the “2-3 clave”, and a second listen to the whole thing can reveal how this feel is used in previous sections (by the drums from 1’33” on and the saxes from 2’05”). It’s no coincidence that both Bauduc and Eddie Miller were actually from New Orleans, where such cross-rhythms were in the water system, but doubtless nobody in the late 1930s was consciously picking up on such things. They were just grooving to a masterful modernisation of traditional ideas, and a zestful performance that never fails to galvanise listeners.

This article originally appeared in the August 2019 issue of Jazzwise. Explore our latest subscription offers today