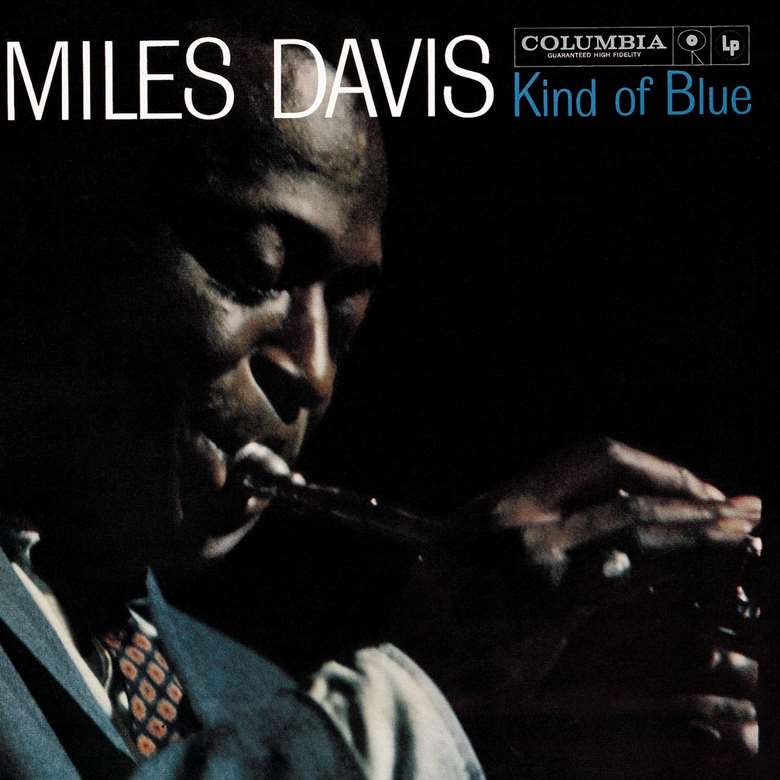

Kind of Blue: how Miles Davis made the greatest jazz album in history

Stuart Nicholson

Saturday, March 13, 2021

Kind of Blue is frequently cited as the greatest jazz album of all time. Stuart Nicholson tells the full story of how Miles Davis, Cannonball Adderley, John Coltrane, Bill Evans, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers and Jimmy Cobb made it

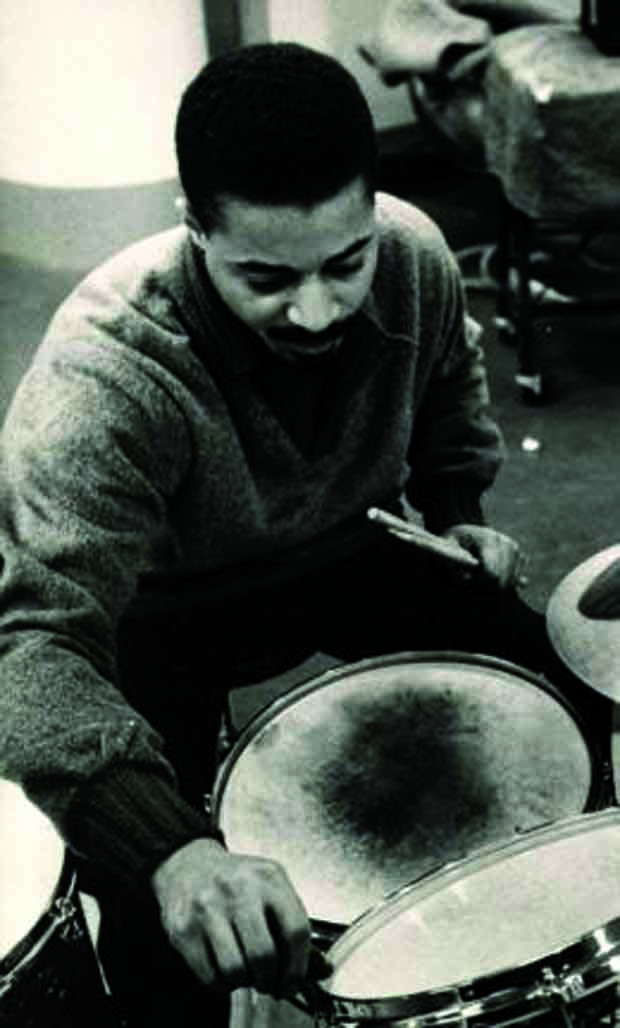

What Miles Davis, had he been alive today, would have made of the sumptuous reissue package Kind of Blue: 50th Anniversary Collector’s Edition is anybody’s guess. Those close to him spoke of his ambivalence towards his past achievements, one moment regarding them with pride, the next as a burden. When, in the 1970s, the great Jimmy Cobb, the drummer on the album that he once described as having been “made in heaven”, was given a rare live tape recorded by the Kind of Blue band shortly before its break-up, he immediately took it around to share with his old boss. “Miles wouldn’t even open his door, telling Jimmy through the intercom to slide it under,” wrote author and critic Eric Nisenson. “Jimmy, who used to be close to Miles and is a very sensitive person, simply left.”

If Davis often gave the impression of running away from his distinguished past during his lifetime, then since his death in 1991 the rest of us can’t seem to get enough of it. Although his prolific creativity ceased when he took a furlough from jazz between 1975 and 1981, his career on records continued unabated as Columbia delved into their vaults to release previously unreleased material. When he made his comeback in 1981, in terms of record releases at least, it was if he had never been away.

Following his death in 1991, there has been a distinct feeling of déjà vu as Columbia embarked on a major reissue series of scrupulously packaged boxed sets of key Davis sessions. With the release Miles Davis/Gil Evans: The Complete Columbia Studio Recordings (Volume 1) in 1996 through to the final The Complete On the Corner Sessions (Volume 8) in 2007, plus The Complete Live at the Plugged Nickel 1965 and The Cellar Door Sessions 1970, each box-set (now highly sought-after collector’s items) dominated the jazz best selling charts and in some cases, such as the Miles Davis/Gil Evans set, remained on the chart for the best part of a year.

Add to this The Miles Davis Quintet: The Legendary Prestige Quintet Sessions box set from the Concord Music Group in 2006, and it seems that Davis still has the power to command our attention in a way no other jazz artist, alive or dead, is able to do today. For many, his crowning achievement was the album Kind of Blue, the best selling album in jazz history. In 1999 it topped The Independent’s “50 Best Recordings of the 20th Century” list, in 2006 it topped the Jazzwise “100 Albums that Shook the World” listing, while more recently The Guardian’s “1000 Albums to Hear Before You Die” gave Kind of Blue a half-page box-out, an honour accorded to just 20 or so albums on the whole list. It even featured at No. 66 on the pop station VH1’s “100 Greatest Albums of Rock ’n’ Roll.”

“It has been the base-station from where countless fans have begun their journey into jazz”

No other recording in jazz has come remotely near acquiring the kind of cachet Kind of Blue has accumulated over the decades. It’s an album that has probably been responsible for more Damascene conversions of non-believers into the jazz faith than any other, it has been the base-station from where countless fans have begun their journey into jazz and it’s an album that crops-up in the record collections of classical, rock, pop and Country and Western devotees who would not otherwise give jazz house room.

“I think for the dilettante Kind of Blue is a lifestyle recording,” says Bob Belden, composer, saxophonist, pianist and producer of over 200 CD reissues of Miles Davis’ recorded music, and three times Grammy winner for his work on the Columbia/Legacy Miles Davis boxed set series. “The music is a sound you can ‘use’ as a background to your life, much in the way Frank Zappa described music for a certain type of listener. I’ve heard the recording at least a thousand times, so it’s more of a ‘brain juke box’ top-10 hit for me and I’m sure many others.”

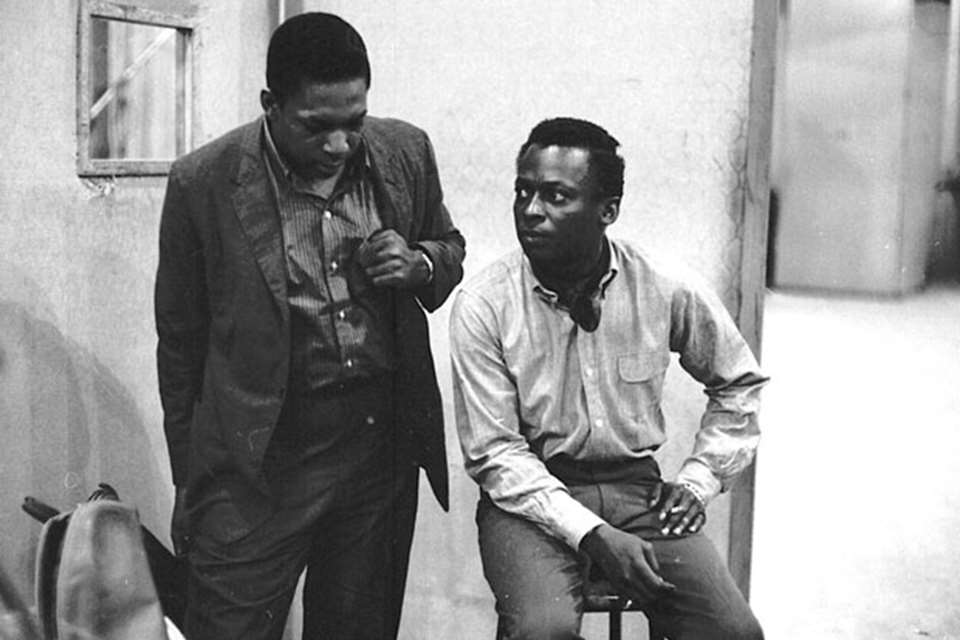

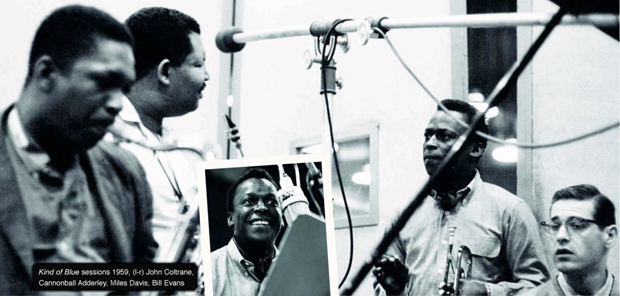

It is all the more remarkable, then, that it was made on the cheap – a few thousand dollars contractual advance to Davis, union scale payment to six sidemen – Julian “Cannonball” Adderley on alto saxophone, John Coltrane on tenor saxophone, Bill Evans or Wynton Kelly on piano, Paul Chambers bass and Jimmy Cobb on drums – nine hours studio time, four reels of tape and a piano tuner’s fee. Recorded on 2 March and 22 April 1959, it has achieved a feat few recordings have ever managed to do by slipping the context of the time in which it was recorded to become a truly timeless masterpiece.

1959 – A Year of Change

Looking back at the year 1959 today, it doesn’t just seem like a different world, it seems more like a distant planet in some far-off galaxy. It was a year when the US Top Twenty hits were songs like ‘Kookie, Kookie, Lend Me Your Comb’ by Edd Byrnes and Connie Stevens that reached No. 4, ‘Tallahassie Lassie’ by Freddy Cannon that reached No. 3, ‘Dream Lover’ by Bobby Darin that made No. 2, ‘Lipstick On Your Collar’ by Connie Francis that made No. 5, while the Chipmunks’ ‘Ragtime Cowboy Joe’ made No. 9, spending a total of 16 weeks on the chart.

Although it wasn’t all instantly disposable teeny pop, Ray Charles’ ‘What’d I Say’ reached No. 6 and spent a total of 15 weeks on the charts, Nina Simone’s ‘I Loves You Porgy’ made No. 18 and Sarah Vaughan’s ‘Broken Hearted Melody’ hit the No. 7 spot, they were slim pickings. 1959, was, after all the year that saw Wink Martindale’s ‘Deck of Cards’ make No. 7, a song that for some unaccountable reason refused to have the good manners of ‘Kookie, Kookie, Lend Me Your Comb’ and disappear forever.

It was also the year that saw the death of three great singers, coincidentally one each from the worlds of classical music, popular music and jazz – Mario Lanza, Buddy Holly and Billie Holiday – and it saw the release of Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, Preminger’s Anatomy of a Murder with a Duke Ellington soundtrack, Cocteau’s Le Testament d’Orphée while Ben Hur swept the Grammy award ceremonies.

The USSR put a rocket into space with two monkeys, Fidel Castro became the President of Cuba, Ingemar Johansson defeated Floyd Patterson to win the World Heavyweight crown, the US Postmaster banned Lady Chatterley’s Lover from the mail on the grounds of obscenity and Los Angeles defeated Chicago in the World Series.

In the UK, the British Motor Corporation put on display its new car called the Mini, costing a little over £500, as compared to the new Rolls Royce Phantom V which cost £8905, and Surrey won the cricket championship for a record seventh successive time. In October, Harold Macmillan called a general election, defeating Labour in a landslide, and one of his new Cabinet ministers, now long forgotten, was to have a lasting effect on all of us. Ernest Marples, the new Minister of Transport, launched a nationwide motorway building programme.

“It sounds fresh, newly-minted and contemporary. And it is here the source of its enduring appeal lies”

If the distance from which we stare at Kind of Blue today can be measured in terms of a United Kingdom with no motorways, then the wonder of it all is that the music does not sound as if it has come out of the same time-capsule that contains ‘Tallahassie Lassie’ or ‘Lipstick on Your Collar’; it sounds fresh, newly-minted and contemporary. And it is here the source of its enduring appeal lies.

Early Modal Experiments

Yet Kind of Blue did not appear out of a vacuum. Miles Davis had been showing interest in modes as a basis for improvisation for several years through his association with George Russell, and an opportunity to harness their potential presented itself during a trip to Paris in December 1957, where he was booked to play the Olympia Theatre, followed by three weeks at the Club St. Germain with a French group. Invited to provide the soundtrack music for Louis Malle’s L’Ascenseur pour L’Echafaud with his French band, Davis improvised in real-time to the screenplay without any pre-written themes using little, if any, harmonic movement (the prevailing tonalities were mostly D minor and F). The following year on the album Milestones, Davis uses modes proper on the title track, which is a 40-bar AABA song form with a different mode for the A and B sections (Dorian and Aeolian respectively).

In August 1958, Davis collaborated with Gil Evans on Porgy and Bess, which numbers among the great orchestral recordings in jazz and became his best-selling album until 1971, when it was overtaken by Bitches Brew. In this lush scoring of George Gershwin’s opera, Gil Evans gave Davis a scale with which to construct his solo (instead of chords) on ‘I Loves You, Porgy,’ while on ‘Summertime’ his solo is effectively based on one chord. This move towards static harmonies would reach its apotheosis on Kind of Blue, in which pianist Bill Evans played a significant role in midwifeing in the way Gil Evans had done at the Birth of the Cool sessions in 1949 and Joe Zawinul would do on the In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew sessions in 1969.

Bill Evans was no stranger to modes. He can be heard on George Russell’s Smalltet on Jazz Workshop (Bluebird) from 1956, essentially using the Lydian scale as a way of negotiating harmonies on minor classics such as ‘Ye Hypocrite, Ye Beelzebub,’ ‘EzzThetic,’ ‘Ballad of Hix Blewitt’ and ‘Concerto for Billy the Kid.’ The latter tune served as a prelude to Russell’s composition ‘All About Rosie,’ a powerful piece of three short movements that appears on Modern Jazz Concert (Columbia/Legacy) recorded in 1957. It was in essence a mini-concerto for Evans, and is an example of Russell’s Lydian concept writ large, and played a significant role in gaining Evans recognition in musician’s circles.

Bill Evans

On Evans’ debut album as a leader, Everybody Digs Bill Evans (OJC), recorded on 15 December 1958, he recorded a solo piano composition called ‘Peace Piece.’ It is based on a repeating two chord pattern that would crop up four months later as the first four bars of ‘Flamenco Sketches,’ the final track of Kind of Blue. But depending on what vinyl album copy of the album you have, you might find that this tune is called ‘All Blues.’ This can be traced back to the original track listing and liner notes of the original vinyl issue of Kind of Blue (Columbia CL1355). Among the memorabilia included in Kind of Blue: 50th Anniversary Collector’s Edition is a facsimile of Bill Evans original handwritten draft for his famous liner notes (they are also reproduced in the end papers of the first edition of Kind of Blue: The Making of a Musical Masterpiece by Ashley Kahn). In them, Evans states in his own handwriting that ‘Flamenco Sketches’ “is a six-eight, twelve measure blues,” and that ‘All Blues’ “is a series of five scales, each played as long as the soloist wishes.” His notes were in turn printed in full on the original issue of Kind of Blue, where the two tunes correspond to Evans’ description.

After the first vinyl pressing, Columbia transposed the song titles on side two, swapping the title ‘Flamenco Sketches’ for ‘All Blues’ and vice versa, ostensibly at Davis’ request to Teo Macero. But Davis would have known ‘All Blues,’ with its ‘Peace Piece’ introduction, was a composition Evans brought to the session. Today, Columbia staffers around at the time are no longer with us, making the full reason for the song title switch difficult to nail-down. On the 1997 CD reissue of Kind of Blue (Columbia/Legacy CK 64935), Evans’ original liner notes were printed in the CD booklet with the sub-heading: “Following are Bill Evans’ liner notes from the original 1959 LP release” but they had been altered to take account of the ‘Flamenco Sketches/All Blues’ song title transposition. It meant Bill Evans’ “liner notes from the original 1959 release” now ascribed “a six-eight, twelve measure blues” to ‘All Blues’ and “a series of five scales, each played as long as the soloist wishes” to “Flamenco Sketches.”

This was simply not the case on “the original 1959 release,” as can be seen, ironically, from the photo of the original sleeve of Columbia CL1355 within the same CD booklet! One wonders what is going on when liner notes by an authority such as Bill Evans are doctored in this way.

This was simply not the case on “the original 1959 release,” as can be seen, ironically, from the photo of the original sleeve of Columbia CL1355 within the same CD booklet! One wonders what is going on when liner notes by an authority such as Bill Evans are doctored in this way.

Interestingly, Ashley Kahn in his book Kind of Blue: The Making of a Musical Masterpiece describes the recording of both ‘Flamenco Sketches’ and ‘All Blues’ using the transposed song titles with Evans’ brief description altered accordingly, so that ‘Flamenco Sketches’ becomes “a series of five scales…” and ‘All Blues’ becomes “a 6/8, 12 measure blues.” In his text he claims that these descriptions were “From Bill Evans liner notes.” They were not. These descriptions were the reverse of Evans’ original handwritten notes reproduced in his own book. In the UK edition of the book, the handwritten notes were cut at ‘So What’. And just to muddy the waters even further, the first CD release of Kind of Blue in the UK (CD CBS 62066) included the late Benny Green’s liner notes from the first vinyl release of the album in the UK, where he refers to ‘Flamenco Sketches’ as a blues in 6/8 and ‘All Blues’ as a series of scales, even though on the CD, ‘Flamenco Sketches’ is a series of scales and ‘All Blues’ is a blues in 6/8. Confused? Don’t be.

Bear in mind Evans was a prime witness – he was on the session at Davis’ special invitation (he had left the Davis group a few months earlier to form his own trio and had been replaced by Wynton Kelly, who played on one track only). Evans played piano on the four key album tracks, discussed each piece with Davis, played a part in arranging the pieces and was, after all, referring to his own composition ‘All Blues’ (with his own “Piece Peace” introduction) when he described it as “a series of five scales, each played as long as the soloist wishes.” He would, you might think, know what his own composition was called.

Bob Belden has suggested that the song titles as Evans describes them are rooted in sound musical logic. “One could say that the ‘flamenco’ suggested in the title was for the rhythmic element of flamenco dancing and not tied to any particular scale or mode definition. The ‘blues’ of ‘All Blues’ could imply the various types of modes that would, intellectually, construe a kind of ‘indigenous blues scale,’ relevant to the particular cultural attachment. What is true is that no one has ever challenged the changes based on a pure music analysis and offered convincing options as those I have suggested.”

Flamenco Sketches

If we go by Evans’ original titles as they appeared on the original vinyl release of Kind of Blue, which Professor Lewis Porter says he believes “were correct” in his book John Coltrane: His Life and Music, then what Evans claimed was ‘Flamenco Sketches’ (identified as ‘All Blues’ on later copies) is a hypnotically swaying minor key twelve bar blues in 6/8, albeit with a simplified first four bars which remain firmly in the tonic key which gives it a “modal” feel. The “rolling” piano introduction is four bars in length, possibly inspired by a vamp Ahmad Jamal uses in a section of ‘Autumn Leaves’ from Portfolio of Ahmad Jamal (Chess) – Jamal was a Davis favourite whose influence surfaces on several Davis albums. This vamp is used between the first and second choruses of the theme, and between soloists. Note how, like ‘Milestones’ from 1958, the piece fades; commonplace now but very rare in 1959.

In contrast, the opening four bars of ‘All Blues’ (if the rhythm of ‘All Blues’ on your copy is ONE-two three-FOUR-five-six, ONE-two-three-FOUR-five-six then you are listening to what Evans claimed was ‘Flamenco Sketches’) follows exactly the opening of ‘Peace Piece,’ albeit with Evans’ left hand (that plays the lowest notes on the piano) given to bassist Paul Chambers – the tune is in a slow four, counted ONE-two-three-four, ONE-two-three-four.

Davis enters on harmon muted trumpet against a piano and bass accompaniment, and then outlines the order of the five modes used for improvisation, and this order is followed in turn by Coltrane, Adderley, Evans and Davis again, although they are free to play on each mode for as long as they want. Here’s how it played out that memorable day at Columbia 30th Street studios, starting with Davis’ solo:

Davis: Mode no.1 – four bars; Mode no.2 – four bars; Mode no. 3 – four bars; Mode no. 4 – eight bars; Mode No. 5 – four bars.

Coltrane: Same structure as Davis

Adderley: Mode no. 1 – eight bars; Mode no. 2 – four bars; Mode no. 3 – eight bars; Mode no. 4 – eight bars; Mode no. 5 – four bars.

Evans: Mode no. 1 – eight bars; Mode no. 2 – four bars; Mode no. 3 – eight bars; Mode no. 4 – four bars; Mode no. 5 – four bars.

Davis: Mode No. 1 – four bars; Mode no. 2 – four bars; Mode no. 3 – four bars; Mode no. 4 – eight bars; Mode no. 5 – two bars.

Note that Adderley chooses the greatest variation of mode lengths. The distinguished critic of both classical music and jazz, Max Harrison called ‘All Blues’ a good example of ‘primitive jazz serialism’ in A Jazz Retrospect, where “instead of a chord sequence, the improvisations are based on a series of five scales, that is five selections of notes from the twelve available. Davis [actually Bill Evans] constructed fragmentary tone-rows which replace harmony in giving the music coherence.”

So What

These tunes, whatever their correct titles, comprised selections one and two respectively of side two of the vinyl releases. Side one opened with ‘So What,’ which, in the cold light of day is simply a 32 bar AABA songform, where the A sections are “D” Dorian mode and the B or middle eight section is “Eb” Dorian mode – precisely the same form and modes that John Coltrane would later use on his composition ‘Impressions.’ The moody introduction with Bill Evans and Paul Chambers was written by Gil Evans and is followed by a “call” by Chambers’ bass followed by a “response” from the band that has its origins in the way Duke Ellington used bassist Jimmy Blanton to dialogue with his orchestra on his landmark 1940 recording of ‘Jack the Bear.’

Davis’ solo is one of the great moments in jazz. It has been learned by heart by almost every aspiring jazz musician on the planet, it has been set to words by Eddie Jefferson and orchestrated for trumpet section on the George Russell album So What (Blue Note) from 1986. The effect of a whole trumpet section playing the solo is startling, revealing the architectonic quality of Davis’ work. It is an effective technique that has the effect of projecting a great solo onto a larger screen. Examples include Tommy Dorsey’s ‘Marie,’ when Bunny Berigan’s memorable solo from January 1937 became a trumpet section soli in the 1940s, and the Quincy Jones orchestration of Clifford Brown’s solo from ‘Stockholm Sweetnin’’ on … This Is How I Feel About Jazz (ABC Paramount) from 1956 and his orchestration of Nat Adderley’s solo from ‘Hummin’’ from the Cannonball Adderley Quintet’s 1963 album Country Preacher (Capitol) on the Jones album Gula Matari (A&M) from 1970.

Freddie Freeloader

‘Freddie Freeloader,’ is an orthodox, straight ahead 12-bar blues, which has pianist Wynton Kelly in place of Evans, and it is interesting how Davis stops the first take of this tune with a whistle because the tempo was too fast – suggesting that he felt a brisk tempo was at odds with the overall mood of the album. ‘Blue in Green’ is a 10-bar theme, unusual in jazz, which the band went over four times, before producing a perfect take. What is interesting is that the piece had a preset chord progression whose duration could be altered by the instrumentalists during their improvisation.

On both the vinyl and CD copies, Davis gets composer credit for ‘Blue in Green’ and ‘All Blues,’ although they were composed by Evans. The three selections from the 2 March session – ‘So What,’ ‘Freddie Freeloader,’ ‘Blue in Green’ – comprised side one of the vinyl release and were recorded on two 3-track Presto all-tube tape recorders – a master plus a safety machine. However, the master machine operating that day was running slightly slower than the industry standard of 15 ips. Unaware of this, the technicians took the tape from this recorder to mix and master Kind of Blue.

Pitch Perfect

For decades, musicians were aware that when playing along with side one of Kind of Blue it was necessary to retune their instruments to a slightly sharper pitch so as to be in tune with the recording. This anomaly was rectified in 1992 with the release of the gold Mastersound reissue of Kind of Blue, using the tape recorded at the correct pitch from the safety machine. The 1997 reissue went a step further, remixing the safety tape (at the correct pitch) and offered the only known alternative take of the whole session, the composition that opens with four bars of Bill Evans’ ‘Peace Piece.’ This additional take is also included on the 50th Anniversary CD (but not on the facsimile vinyl album also included in the set) and adds additional studio chatter and false starts not previously released from the session.

The after-the-fact rationalisation of pitch correction has its critics, especially those who grew up with the slightly sharp version of the original vinyl side one. But Guy Barker, the award winning UK trumpeter, points out that the corrected version is “How it sounded when they played it. I think that is important for us to hear. The danger is that when something is slightly faster, slightly brighter and slightly sharper and that gets taken away the feeling might be, ‘This will be slightly slower, slightly dull and less bright and maybe less exciting,’ so immediately we’re throwing negative language at it. But here the difference is so slight that what it might do, if anything, is slightly broaden the sound and it might be intriguing to hear the true tempo of it, and the true sound of it. I don’t think it’s a bad thing, I think it is good in fact.”

“This is the soul of Miles Davis and it is a beautiful soul”

Downbeat magazineKind of Blue (Columbia CL1355) was released in the USA on 15 August 1959, to immediate acclaim. “This is a remarkable album,” said Downbeat magazine, giving it a maximum five-star rating. “Using very simple but effective devices, Miles has created an album of extreme beauty and sensitivity… this is the soul of Miles Davis and it is a beautiful soul.” Later in the 1959, Columbia released Jazz Track (Columbia CL 1268) which included the original music to L’Ascenseur pour L’Echafaud on side one, while side two comprised ‘On Green Dolphin Street,’ ‘Put Your Little Foot Right Out/Fran Dance,’ and ‘Stella by Starlight’ thus completing the studio recordings of the Kind of Blue band, albeit with the exception of ‘Love for Sale’ (all the tracks are included on the 50th Anniversary set). Once again Downbeat awarded five stars, “The New York date is top notch Davis of recent vintage,” noted reviewer Ralph Gleason, “The other horns stand on an equal basis with their leader.”

What is striking at this remove is the recording quality of Kind of Blue and the fact it was essentially a studio creation whose music had no life (except for ‘So What’ and the blues in 6/8, called either ‘All Blues’ or ‘Flamenco Sketches,’ depending on who you believe) beyond it. Perhaps the near perfection in recorded sound achieved on this album also contributes an element that has added to its timelessness, as Bob Belden explains: “The simple fact is that most of the music from Kind of Blue never made it to the concert stage for further exploration,” he says. “When it did, the emotional element of the music that was the underscoring of the studio session did not exist in a live format. One makes certain sounds in an ambient studio, using a certain kind of dynamic, enabling a different way the inner ear hears the instrument; this is what makes Kind of Blue stand out as a musician’s reaction to an environment, whether it be in front of an audience or in a studio. Fred Plaut was a highly educated and responsive engineer, trained in classical recording techniques, and that was a big difference. Listen to the Frank Laico recorded Milestones compared to the Harold Chapman recorded Jazz Track and then Fred Plaut’s Kind of Blue. A difference in the use of space by the engineer, and dynamics and arrangements for the musicians. Pure professional and artistic choices. And the results are born out in the contrasts of recorded styles.

With Milestones they were recording the hardest of hard bop. Jazz Track [recorded in 1958] was a real masterpiece in that the way the music was arranged and recorded and it became the model for Miles’ recording from that point on. Harold Chapman was a commercial engineer who specialised in vocals. So he could really get a romantic sound out of Miles and Bill Evans and that was partly due to the subdued nature of the music, which partly may have been influenced by the ambient nature of the studio. Conjecture, I admit, but based on experience in a recording environment.

It is also worth noting that the sound of Kind of Blue was an important influence on record producer Manfred Eicher, helping him shape an aesthetic towards recorded sound that has informed over 1,000 albums on the internationally renowned ECM label.

Critical Reception

The UK saw Kind of Blue released under licence from Columbia on the Fontana label (an imprint of Phillips) in late February 1960 in mono and May 1960 in stereo. It is interesting to note that during an 18-month period between May 1959 and November 1960, no less than ten different studio albums and several EPs by Miles Davis were released in the United Kingdom during this period through both Columbia and Prestige.

You might be forgiven for thinking critics of the time might have suffered from Davis overload during this period, but not a bit of it. Kind of Blue seemed to have been released at just the right moment in the UK as in the month prior to its release the headline on the front of Melody Maker (30 January 1960) blazed-out “Miles Ahead Of Louis – Miles Davis has done the impossible! For the first time in the history of the Melody Maker Readers’ Poll, Louis Armstrong has lost his title as the World’s Top Trumpeter.” And in the following month’s Melody Maker’s Critics’ Poll most critics chose either Davis or Armstrong, with Davis coming in second place only to Duke Ellington as Musician Of The Year, Davis winning in the Small Combo category and coming joint first (with Armstrong) in the Trumpet category. So there must have been high expectations by the time Kind of Blue was released in the UK. Indeed, some British fans had probably already read American reviews of the album in Downbeat which had appeared in the 1 October 1959 edition. The reviews from the main gatekeepers of UK jazz culture of the time were uniformly enthusiastic, bearing out Davis’ growing reputation in the polls and despite the number of Davis releases during this period. In Jazz Journal, Kennedy Brown offered this prescient review: “My advice is to rush out and buy this disc immediately. It is one of the best jazz discs I have heard so far this year. For that matter it is one of the best jazz discs of any year. It is also possibly the best record to date by Miles Davis… It’s my opinion that this disc confirms the stature of Davis as the greatest soloist since Louis Armstrong. This disc is also a pointer to the way that jazz can-and-will-develop.”

In its main competitor magazine, Jazz Monthly, Charles Fox also demonstrated insight into the album in his opening remarks, going on to enthuse: “The more years that roll by, the more blasé one tends to become about new records. Yet… I was again swept off my feet by ‘Blues in Green’ [sic] and ‘All Blues’ [the version that begins with ‘Peace Piece’]…” In Melody Maker, the response was just as positive, with the headline, “Magnificent Miles Davis” with Bob Dawbarn’s review claiming that: “On this superb record which provides yet more proof that, far from standing still, Miles is getting farther and farther ahead of his contemporaries.”

After Kind of Blue

Yet for Davis, having completed what today is probably considered one of the greatest jazz albums of all time on 22 April, it was business as usual. On 29 April he closed at Birdland after playing a week with his sextet alongside the Gil Evans Orchestra before heading for Chicago where he closed at the Sutherland Lounge on 18 May. He played the Blackhawk in San Francisco in June, and Jazz Seville in Los Angeles (where the band was reviewed in the 6 August edition of Downbeat magazine), the Canadian Jazz Festival, The Regal in Chicago and the Lick Festival in France in July. In August he was at the Playboy Jazz Festival in Chicago, the Berkshire Music Barn in Lennox, and on Thursday 13 August the sextet opened a two week stay at Birdland.

At the time, according to Downbeat’s New York editor George Hoefer, New York was “like a volcano.” A number of youngsters between 14 and 20 had been killed in gang rumbles, and an attempt to arrest a drunken woman attracted a crowd of hundreds in Harlem and almost sparked a riot. As Downbeat noted: “With teen-age and racial troubles at boiling point, police are reported to be tense, worried, and, in the case of some, frightened.”

It was into this torrid atmosphere that Miles Davis stepped after completing an Armed Services Network broadcast from Birdland on the night of Tuesday 25 August, towards the end of his two week residency. As he emerged into the hot, sultry night-air of Broadway at 52nd Street, Downbeat reported he had an exchange with Patrolman Gerald Kilduff that resulted in a ferocious attack with nightstick, assisted by Detective Donald Rolker with some witnesses claiming the issue was over Davis escorting a white woman to a taxi. Downbeat said “something close to a dozen witnesses interviewed by New York newspapers said Det. Rolker was drunk… Almost all witnesses, including alto saxophonist Julian Adderley, made accusations of police brutality, saying the beating was excessive and unnecessary.”

Photos of Davis after the beating are shocking, indicating considerable blood staining on his suit with his head swathed in bandages. The shameful story made headlines around the world: “This Is What They Did To Miles” recoiled Melody Maker in their 12 September edition. Davis was arrested, charged with assault and disorderly conduct released on $1,000 bail with his temporary Cabaret Card taken from him. Later Al Manuti, president of the American Federation of Musicians demanded an enquiry into police brutality. Subsequently, the assault charge was reduced to one third degree assault enabling Davis to have his Cabaret Card back. But during the interim he had been unable to work without a Cabaret Card and the Kind of Blue band broke-up. Months later all charges were dropped.

Photos of Davis after the beating are shocking, indicating considerable blood staining on his suit with his head swathed in bandages. The shameful story made headlines around the world: “This Is What They Did To Miles” recoiled Melody Maker in their 12 September edition. Davis was arrested, charged with assault and disorderly conduct released on $1,000 bail with his temporary Cabaret Card taken from him. Later Al Manuti, president of the American Federation of Musicians demanded an enquiry into police brutality. Subsequently, the assault charge was reduced to one third degree assault enabling Davis to have his Cabaret Card back. But during the interim he had been unable to work without a Cabaret Card and the Kind of Blue band broke-up. Months later all charges were dropped.

The disgusting Rodney King-like beating Davis suffered at the hands of the New York Police Department makes a tragic sequel to what is one ofm the greatest artistic achievements of the 20th century. It had a profound – maybe traumatic – effect on the trumpeter. One biographer, Jack Chambers, suggests it resulted in his music plateauing since he did not get back into his creative stride until 1964. Indeed, during that time he wrote no new music, tried no new settings and did not experiment further with modes. Seventeen years after the event, in an interview in 1976 with Sy Johnson in Jazz Magazine, Davis bitterly raised the issue of his beating apropos nothing at all:

Davis: “I mean, a policeman grabbed me around the neck.”

Johnson: “Why?”

Davis: “Because I was black...”

Johnson: “Is it gonna be OK?”

Davis: Shrugs.

As the distinguished American commentator Martin Williams noted, “ Kind of Blue was an influential record both in and of itself and because it paralleled other, independently conceived events in jazz. But for a while it seemed a rather isolated event for Davis himself – one might say it was more immediately important to John Coltrane’s development than to Davis, and for the next few years the repertory of ballads and standards was resumed to a great extent.” It would not be until he was joined by pianist Herbie Hancock, bassist Ron Carter, drummer Tony Williams and saxophonist Wayne Shorter that Davis’ career regained creative momentum. The tragic postscript to Kind of Blue, played out on the sidewalk outside Birdland that fateful night in August 1959, didn’t just leave physical scars, it ran deep.

This article originally appeared in the December 2008 / January 2009 issue of Jazzwise. Subscribe to Jazzwise.