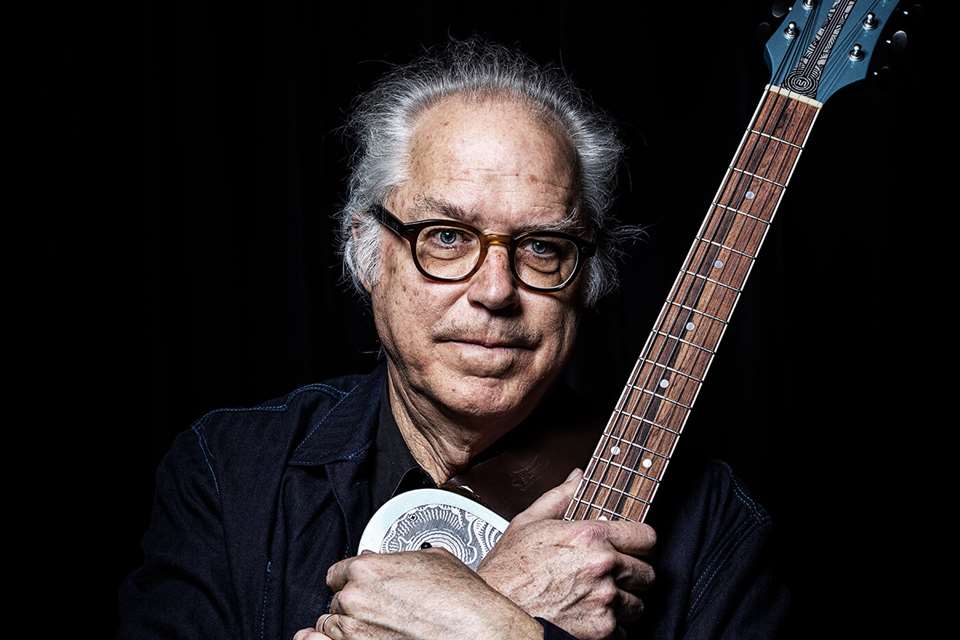

Bill Frisell interview: “I hear a song and have to ask myself if it’s remembered or new”

Alyn Shipton

Wednesday, January 29, 2020

Bill Frisell’s latest album, HARMONY, is the first outing under his own name for the legendary Blue Note label. Alyn Shipton spoke to the influential guitarist about the origins and evolution of this song-heavy project, which features the vocal delights of Petra Hayden (daughter of Charlie), as well as his recollections of working with the late-great Ginger Baker

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting Jazzwise.co.uk. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, live reviews and artist pages

- Free email newsletter