Charles Lloyd: “The thing is I want to share the music. I’m still on a mission and it can’t happen – this is plague time…”

Stuart Nicholson

Tuesday, June 23, 2020

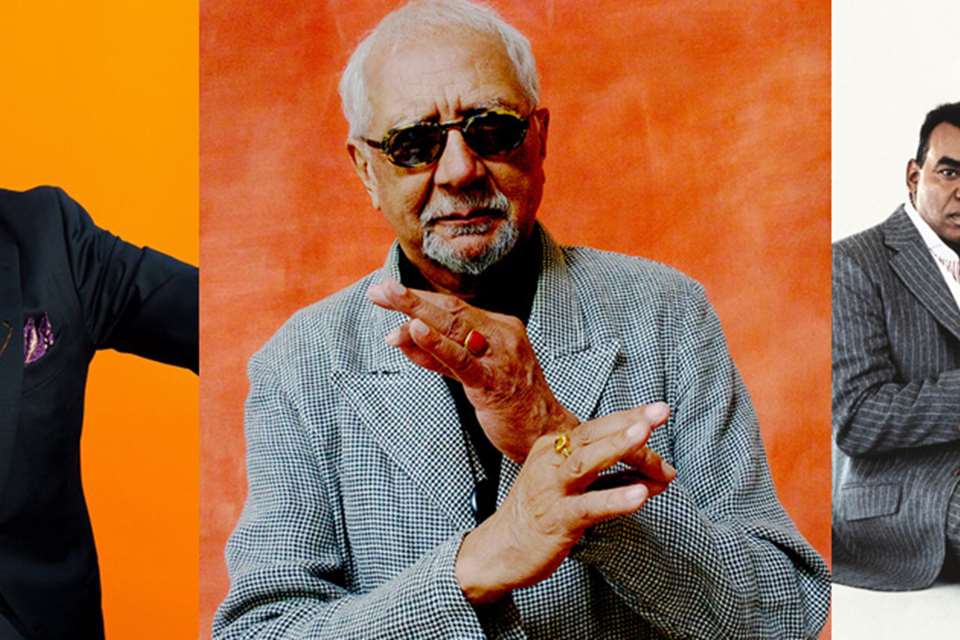

For some artists, the twilight years can be a time to reflect and review a lifetime’s work. But, for saxophonist Charles Lloyd, his 80th birthday in 2018 provided an opportunity to bottle his eight decades into a single staggering live performance that’s just been released as a mind-blowing double album. More than a mere greatest hits collection, 8 shines new light on this celebrated musician’s life’s work. Stuart Nicholson caught up with the tenor titan to find out more about that very special night and about his long life and stellar career

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting Jazzwise.co.uk. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, live reviews and artist pages

- Free email newsletter