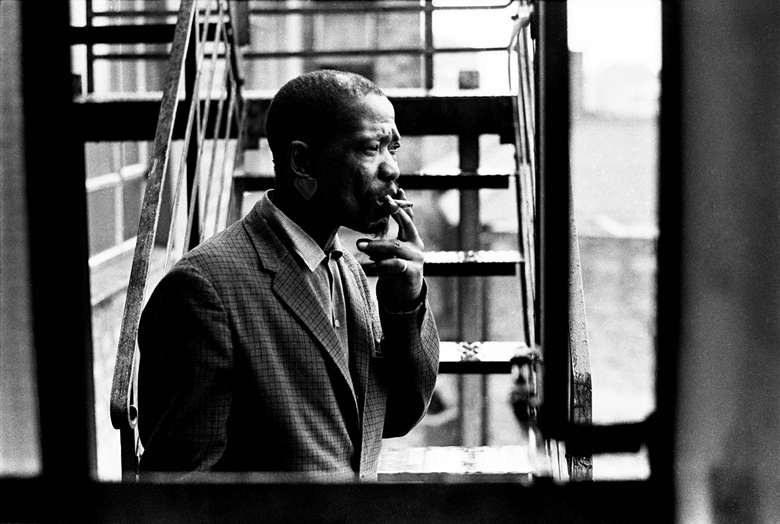

Kippie Moeketsi and the birth of South African jazz

Stuart Nicholson

Wednesday, July 6, 2022

South Africa’s contribution to jazz remains one of the music’s great untold stories. Stuart Nicholson looks at the birth of the country’s jazz scene

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting Jazzwise.co.uk. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, live reviews and artist pages

- Free email newsletter