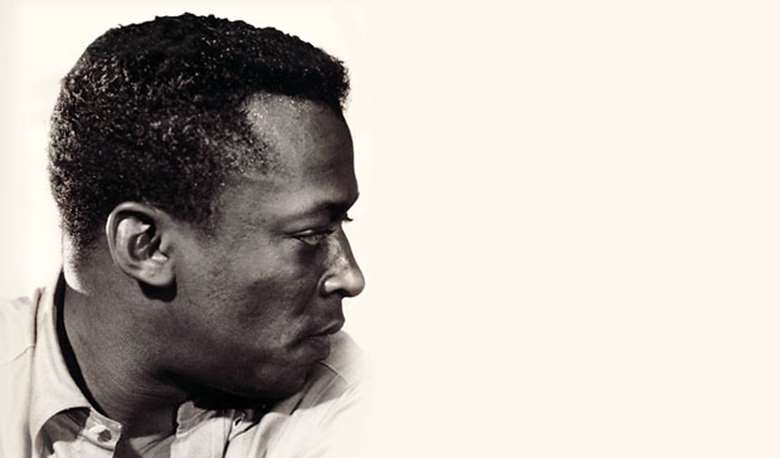

Miles Davis – highs and lows at Newport

Thursday, April 21, 2016

When the Newport Jazz Festival began in 1954, it became a barometer for all that was hot in jazz in 1950s America.

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting Jazzwise.co.uk. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, live reviews and artist pages

- Free email newsletter