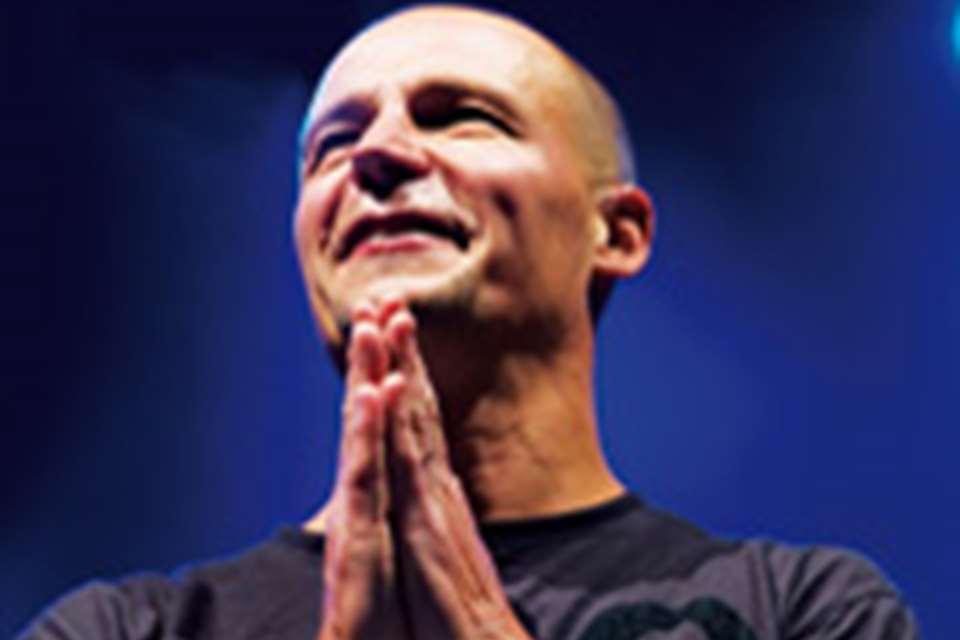

Esbjörn Svensson and Jan Johansson: the tragic catalysts

Stuart Nicholson

Tuesday, July 23, 2019

The 14 June 2018 marks the 10th anniversary of the tragic death of Esbjörn Svensson, just as he was on the cusp of global stardom. Stuart Nicholson examines the primary influence of fellow star-crossed pianist Jan Johansson on this game-changing musician and laments how both artists had much unfinished business ahead of them

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting Jazzwise.co.uk. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, live reviews and artist pages

- Free email newsletter