Sonny Rollins

Kevin Le Gendre

Wednesday, February 17, 2021

Sonny Rollins' improvisations are a stream of brilliant ideas on phrasing, timing and timbre that enable him to skate over a given chord sequence for endless bars without losing the listener’s interest

Rollins carries an important mantle. At 84 he is one of the last men standing from the golden age of bebop and modern jazz, a musician who, although at one time in his life was plagued by the narcotics that did for some of his peers, has nonetheless become a great survivor.

He has also proved to be one of the greatest improvisers of all time, a player who helped to extend and enrich the vocabulary of the saxophone while more or less keeping faith in the core musical principles to which he was inured during his childhood in post-war New York.

Rollins has retained a distinct element of dance in his aesthetic that can be traced right back to the social events and family functions he attended in the city’s West Indian community [his parents hailing from St.Thomas, Virgin islands], where calypso was very much the order of the day.

Throughout the decades ‘Don’t Stop The Carnival’, one of the great standards of the genre, would be his signature tune, and it charmed audiences the world over, adding to Rollins’ stature as a great communicator as well as improviser. Yet it is his phenomenal ability as a soloist that has secured his place in history.

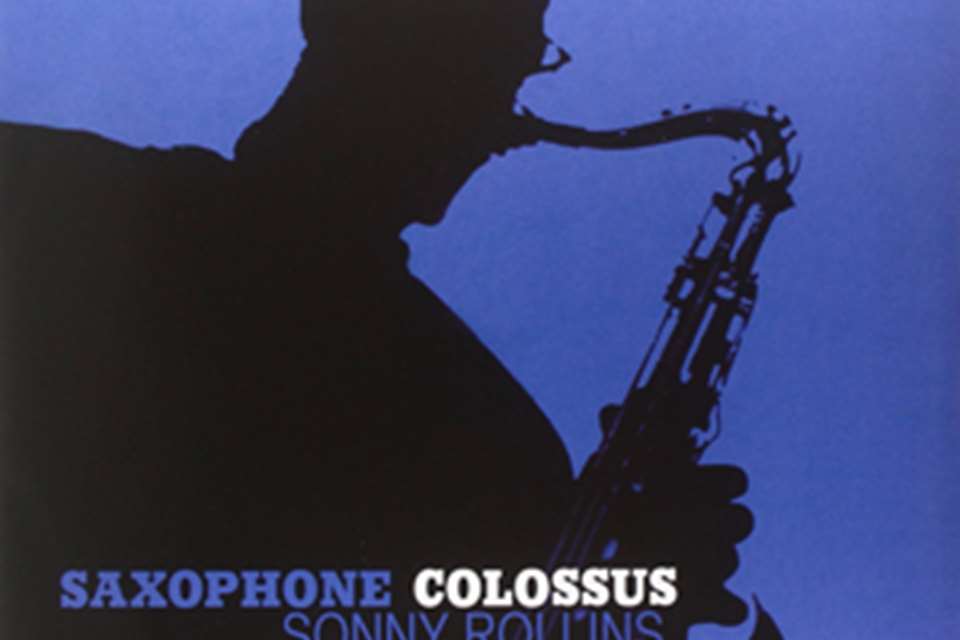

Former sideman to Miles Davis, Tadd Dameron and Thelonious Monk, Rollins grew rapidly in the ‘50s so that by the time he recorded Saxophone Colossus mid-decade he was ready to scale the heights suggested by the title. His improvisations are a stream of brilliant ideas on phrasing, timing and timbre that enable him to skate over a given chord sequence for endless bars without losing the listener’s interest, as he goes about expanding and contracting lines, shaping and re-harmonizing to create a wealth of new colours and sensations.

He continued to do this on melodies drawn from any source, as his stunning take on Johnny Mercer’s swingin’ country & western staple ‘I’m An Old Cowhand’ [from the album Way Out West] attests. With his tone at its most sensual and his thematic variations all lyrical elegance Rollins draws out a deeply affecting sense of nostalgia and longing that really fulfils the ideal of the horn player who conveys as much with notes as a singer does with words.

Although Rollins is undoubtedly one of the great interpreters of standards he has also written several notable originals himself, of which St.Thomas, Airegin and the politically motivated Freedom Suite are fine examples.

Enormously devoted to his craft Rollins withdrew from the club scene for two years in the late ‘50s in order to reassess his work, particularly in light of the arrival of New music’s enfants terribles such as Ornette Coleman and Albert Ayler, and practiced diligently on the Williamsburg bridge [referenced on The Bridge, featuring Coleman’s great sideman, cornet player Don Cherry and guitarist Jim Hall].

Although his musical bedrock has been changes-based post-bop Rollins has also pursued the more abstract pathways of the avant-garde, and his former student, the late David S.Ware contended that Rollins would shock people if he ever gave vent to his ability as a free player. As a musician he is well beyond any issues of sub-genre.