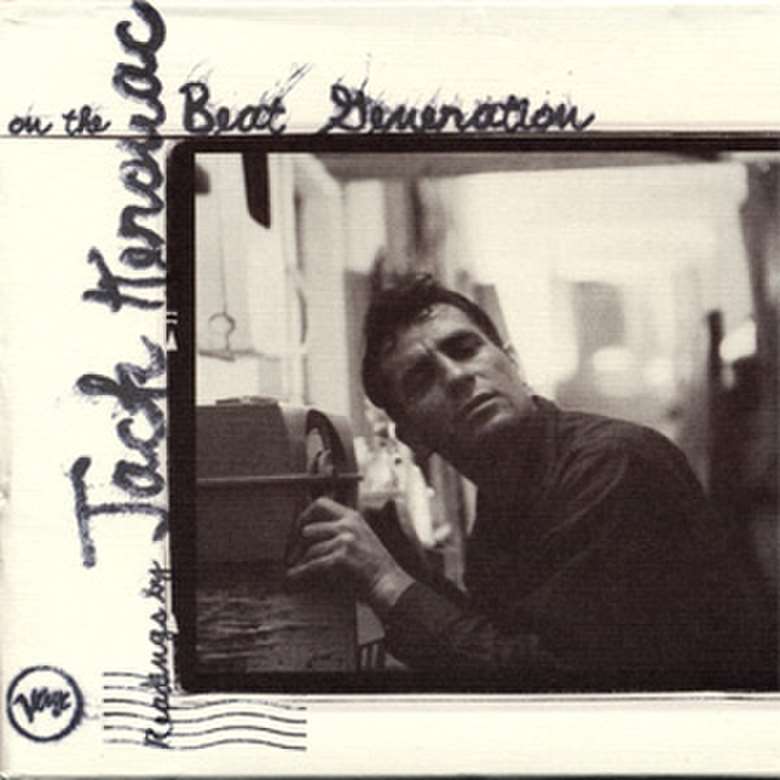

Jack Kerouac and Jazz: “I want to be considered a jazz poet blowing a long blues in an afternoon jam session on Sunday”

Keith Shadwick

Monday, November 15, 2021

Jack Kerouac's 'On the Road' did for literature what Charlie Parker and John Coltrane did for jazz, whipping it up into brave new shapes and forms that challenged the norm and set a generation in motion, writes Keith Shadwick

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting Jazzwise.co.uk. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, live reviews and artist pages

- Free email newsletter