Miles Davis at the 1970 Isle of Wight Music Festival: What really happened

Jon Newey

Tuesday, October 12, 2021

Miles Davis played the biggest gig of his career when he brought his groundbreaking new Bitches Brew band to the 1970 Isle of Wight Music Festival, still the largest ever music event to take place in the UK. Jon Newey was there to witness this historic weekend

By midday on Saturday 29 August, the writhing sea of flesh flowing into the already over-crowded and primitive infrastructure of the vast makeshift arena was on an unprecedented scale, and more were arriving every minute. From the stage the size of the audience must have seemed beyond imagination. The numbers for the 1970 Isle of Wight Music Festival estimated by the Guinness Book of World Records were between 600,000 – 700,000, which still remains the biggest audience for a music festival in the UK. Often referred to as Britain’s Woodstock, and somewhat overshadowed in the media by that 1969 landmark American event, they both shared the dubious distinction of being declared a free festival after the attendance grew unmanageable and was overrun by tens of thousands of ticketless hippies. In the IOW’s case, a contingent of French anarchists and revolutionaries, protest-hardened from Paris 1968, also showed up and toppled fences, insisting all music should be free. Interestingly there was nary a Bobby in sight.

For Miles Davis, used to playing smoky jazz clubs with audiences up to 300 or so plus the odd summer jazz festival such as Newport, where the audience numbered around 5,000, the sheer mass of humanity stretching as far as the eye could see that weekend of Friday 28 - Sunday 30 August must have shaken even his suave demeanor. In the event, it would turn out to be the biggest audience that he, or any other jazz musician, would ever play for.

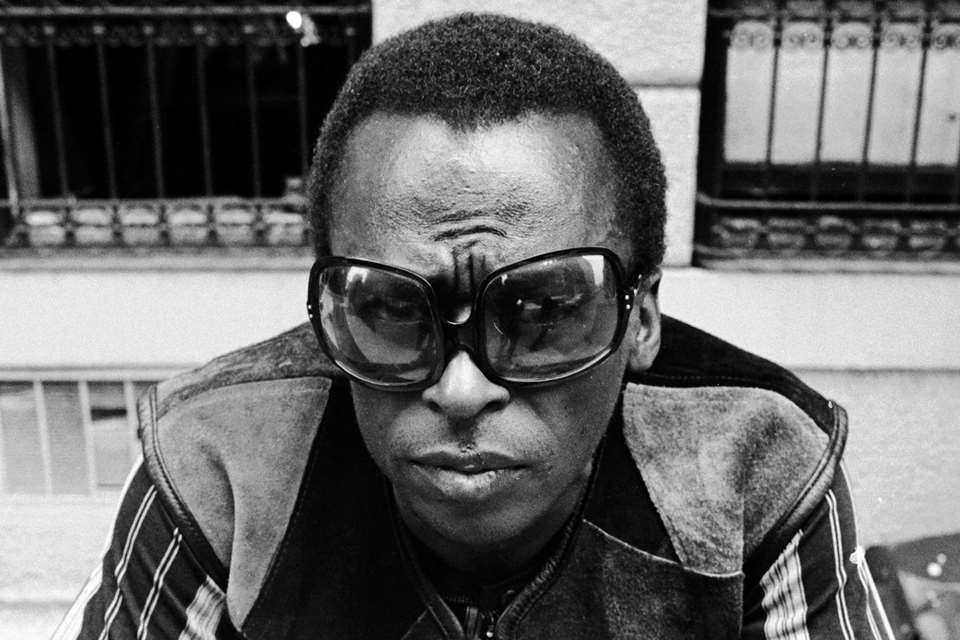

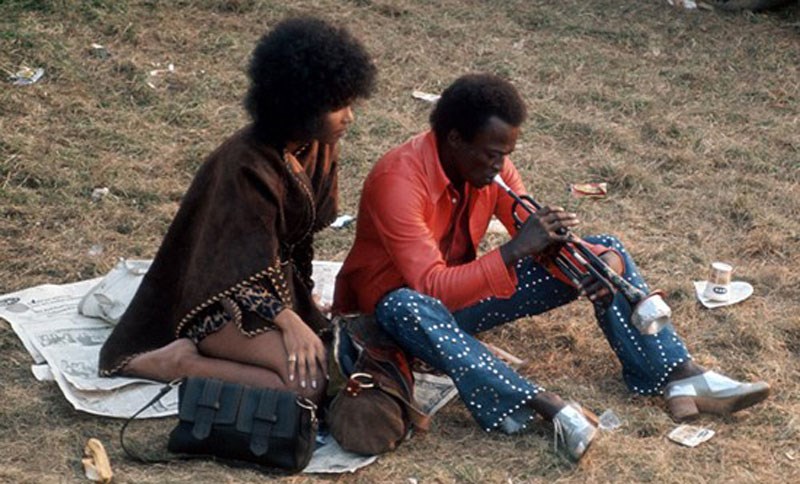

Miles Davis at the 1970 Isle of Wight Music Festival (photo: Charles Everest)

Davis, then 44, and one of the final names to be added to the bill, knew the scene was changing – and how. Jazz clubs had been closing down and reopening as rock clubs and discotheques, and the young collegiate audience that jazz had attracted from the late 1940s, through the 1950s and into the 1960s was fast moving to the new underground rock music, influenced by blues, jazz, folk and psychedelia.

Davis knew he had to remodel or be sidelined by fast changing events and his new electric band, who’d recently played the hippie shrines, San Francisco’s Fillmore Auditorium and New York’s Fillmore East, could stand tall both musically and visually among the forward-looking, cross-genre IOW festival line-up, which ranged from rock giants Jimi Hendrix, The Who, The Doors, Free, Jethro Tull and Emerson, Lake & Palmer to the powerhouse funk and soul of Sly & the Family Stone and Voices Of East Harlem; key singer-songwriters, Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell and Joan Baez, folk-jazz artists such as Pentangle, Richie Havens, Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso, and jazz influenced, horn-laden rock bands Chicago and Lighthouse.

Some of the critics were talking about how aloof I was, but that didn’t bother me; I had been this same way all of my life

Miles Davis

The underground paper Friends (later known as Frendz) referred to Miles’ addition as ‘the strangest choice of the festival… definitely the most musically satisfying,’ while Record Mirror ventured: “Miles Davis is going to be the one to watch. Miles is going to give the Isle of Wight that extra dimension”. And they weren’t wrong.

The festival line-up echoed the wide-open eclectic taste of the period as many rock fans were ravenous for new music while discovering jazz for the first time – hardly a giant step considering most rock bands of any worth then improvised at length and spoke freely of their jazz influences. There was talk too of Miles and Hendrix getting together afterwards to record in London, possibly with Gil Evans.

However, Miles went back to New York and Hendrix to three European festival dates before returning to London and tragically dying on 18 September of inhalation of vomit due to barbiturate intoxication. A potential meeting of the spirits, so near but yet so far.

We were flown in by helicopter because of traffic. Seeing all those people was a really awesome feeling, this is what Miles had wanted to get to and there it was. We were all pretty blown away. Jazz bands had never played for that big an audience before. It was also one of the best performances that we played as a band

Jack DeJohnette in conversation with Stuart Nicholson, June 2020

When I first pitched up on Friday lunchtime at the East Afton Farm site, situated on the island’s western flank, the mellow sunrise had soon cast aside any early mist to reveal a gloriously hot day, which thankfully dictated the weather for the entire weekend. The audience had already expanded out of the festival site up the side and length of Afton Down, now dubbed Devastation Hill, much to the organiser’s annoyance. It was a vast, undulating encampment of tribes, tents and Tibetan scarves, wreathed in marijuana, cigarette and incense smoke and gathered before the largest outdoor stage and WEM PA speaker towers constructed up to that point. A veritable temple of sound for a generation in motion.

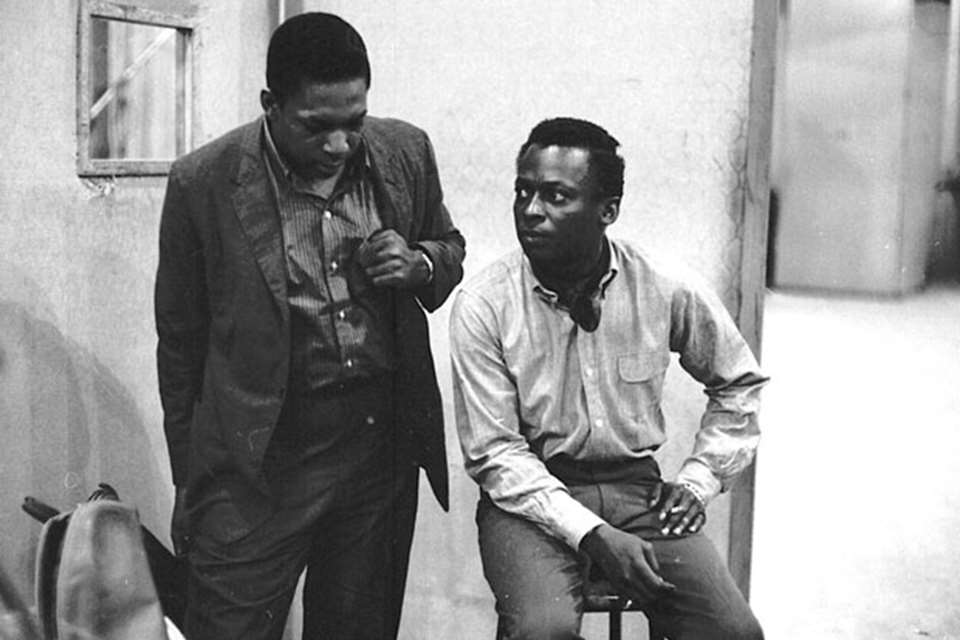

When Miles arrived on the island he was accompanied by his girlfriend Jackie Battle, (not Betty Davis who gets tagged in photos, according to Miles’ autobiography) and his band, now including new saxophonist Gary Bartz alongside Keith Jarrett, Chick Corea, Dave Holland, Jack DeJohnette and Airto Moreira.

In the 12 months since recording Bitches Brew and turning the jazz world on its head, his foot had barely been off the pedal. Not content with forging a whole new direction with this iconic recording, he’d also cut the tracks that later became Big Fun, as well as recording Jack Johnson, tracking three live albums, Live-Evil, Black Beauty and At Fillmore, (all released in 1971), and playing numerous concerts in the USA and Europe.

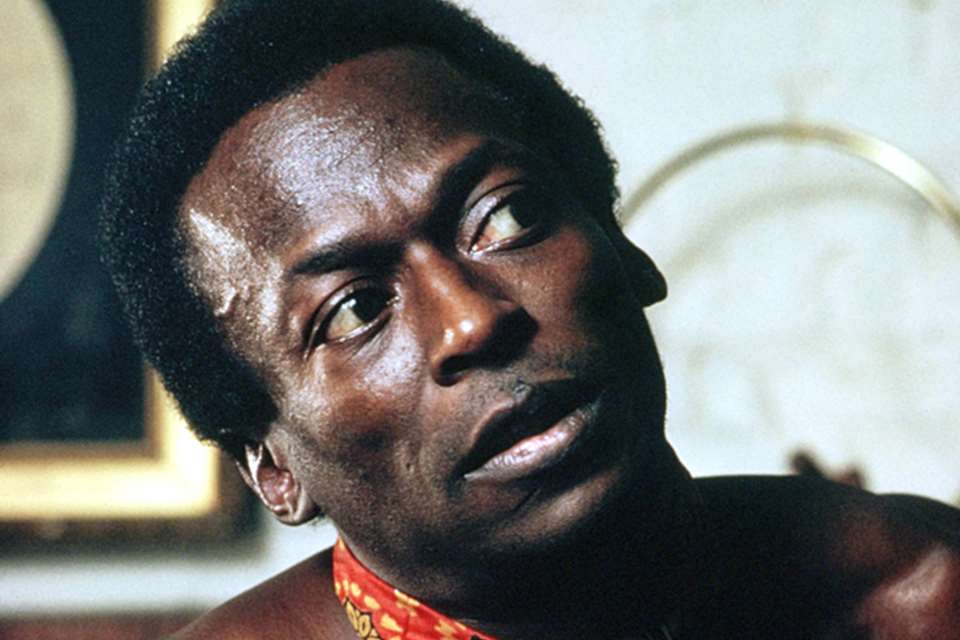

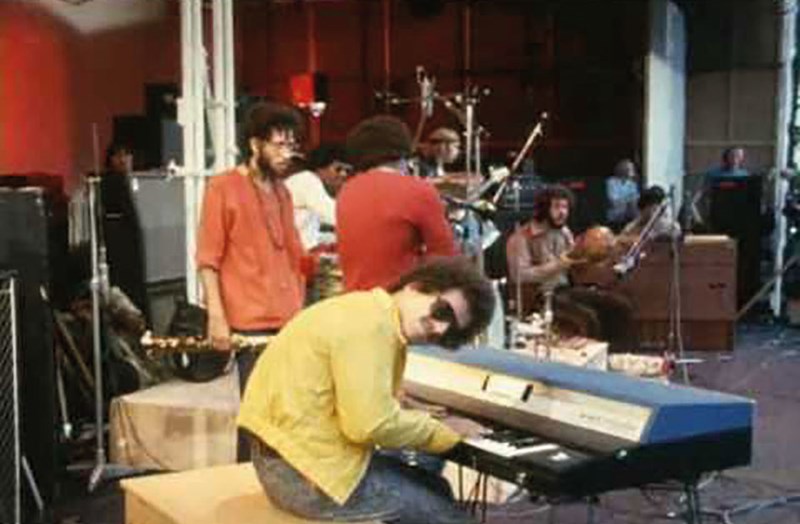

Keith Jarrett in a trance (photo: Eagle Rock Entertainment)

At the IOW festival, the presence of producers Teo Macero and engineer Stan Tonkel, along with the Pye Mobile Recording Studio suggested the tapes would be rolling here too. Just as well, as this extraordinary, short-lived line-up only lasted three concerts. A week before, on 18 August, they played the Berkshire Music Center in Tanglewood, Massachusetts on a bill sandwiched between Santana and Voices of East Harlem, and the Isle of Wight turned out to be their final performance. Barely two weeks later Corea and Holland quit to form Circle with Anthony Braxton and Barry Altshul

By the Saturday afternoon the playful peace ‘n’ love atmosphere began to get a little frayed around the edges, with drug squad officers dressed in hippy clothes infiltrating the crowd, and confrontations between gatecrashers and hired security guards with Alsatian dogs. Joni Mitchell’s solo acoustic set was first disrupted by a noisy helicopter which had the audience booing and shouting at it, before being further unsettled by an American hippie known as Yogi Joe, who Mitchell had previously known from a yoga session. He’d crawled onto the stage and sat by her piano before attempting to grab the microphone to speak to the crowd. Rapidly he was grabbed and dragged off stage where he continued to berate the organisers about how it should be a free festival. His incursion had Mitchell briefly in tears, though she finished her set to a standing ovation.

Meanwhile, Miles had showed up prior to Mitchell taking the stage and was introduced to her by festival MC Rikki Farr before he wandered backstage to hang-out by the mobile recording unit, talking with Macero. His moody, aloof glare suggested he didn’t exactly share the festival’s community spirit, a point that was picked up by Melody Maker in its post-festival coverage. Somewhere it hit a nerve and stayed. Two decades later Miles referred to it in his autobiography: “Some of the critics were talking about how aloof I was, but that didn’t bother me; I had been this same way all of my life.”

Miles pointed his midnight blue lacquered, gold-etched horn at the sun’s descending rays, narrowed his eyes and let rip with a feral, morse code-like blast

The festival’s DJ Jeff Dexter, a key figure on London’s underground music scene since 1967, was backstage where the atmosphere veered between late running chaos and hippie cool as Tiny Tim’s psychedelic vaudeville entourage arrived for their afternoon set.

“I attempted to engage Miles in conversation but he was somewhat negative about the rock bands, festival vibe and Tiny Tim’s wacky antics,” says Dexter. “He didn’t really talk much, though Rikki Farr, who was a big Miles fan, was embarrassingly all over him. Miles’s attitude was certainly in contrast to most of the other musicians.”

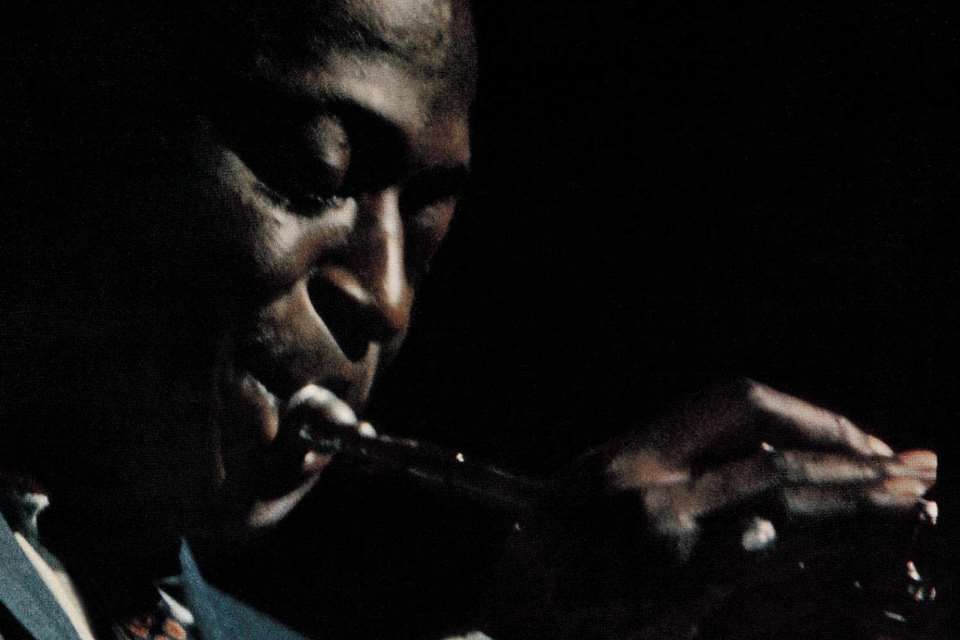

But now though it was the trumpeter’s turn. As dusk approached, the band cranked up a jagged funk vamp before Miles took to the stage, street-cool in red leather jacket, studded jeans and silver stack-heel shoes. While some artists were, not unnaturally, overawed by the vast size of the audience, Miles and the band appeared unfazed and slammed into their set with such ferocity that it jerked the audience around me from its stoned afternoon ennui into a bustle of excited head-turners. Miles pointed his midnight blue lacquered, gold-etched horn at the sun’s descending rays, narrowed his eyes and let rip with a feral, morse code-like blast. This was jazz Jim, but not as we knew it.

Underpinned by the relentless drive of Dave Holland’s circular James Brown-like electric bass figure, Jack DeJohnette’s hustling boogaloo and Airto’s nagging cuica, Miles squirted hard clusters of notes and jabbing trills, freezing the front rows with his terse boxer’s stare before Gary Bartz stepped forward to double with him on ‘Directions’ angular theme, uncoiling into a snaking, eastern tinged soprano improvisation. The tension built, the band empathy locking into a thick, churning groove stretched every which way by the warp-factor keyboards. Miles dipped his head and on cue the band turned down the heat as he breathed a languid five note motif over a deep reverberating bass drone and rattling shekere, signaling the route to ‘Bitches Brew’. Amidst the dust, heat and chaos of this enormous event, and surrounded by the loudest, most electric line-up he’d yet played with, Miles was still and centered, listening hard to the music’s in-the-moment creativity, navigating direction with ‘coded-phrases’ as this continuous modal free-funk improvisation pushed the “sound of surprise” into another dimension.

We helicoptered in. It was totally chaotic. A surreal experience standing on stage in front of the mass of people. Hard to tell what they got from the stage or what they didn’t get. It seemed to be like a massive beach party. Backstage was even more chaotic than out front. That was a fun band though! It was nice to see so many people enjoying hanging out together. For me it was a blip in time. The real thrill was playing with Miles and that band. Keith and I were on opposite sides of the stage. His instrument and my instrument sounded awful. The trumpet, saxophone, drums, percussion and bass won the day.

Chick Corea in conversation with Stuart Nicholson, June 2020

He opened out on long sustained trumpet notes and pinched squeals while Holland and DeJohnette nudged the ebb and flow, ratcheted the pressure and built a deeper, smoking funk force, almost Meters-like in its greasy swagger. Jack’s wide grin and Holland’s boyish smile told all, it was as though the music was playing them. Bartz re-entered the fray with a slow burn alto solo while Corea, poised and purposeful, wound slippery lines around the more experimental Jarrett, whose head and body vibrated to every note, twisting and turning, dipping and diving, lost in a personal dance with the music.

In the space of the 11 days since Davis played Tanglewood (recorded by Columbia and finally released as part of Bitches Brew 40th Anniversary box set), the band now sounded harder, funkier and in places freer. Corea and Jarrett may have been using inferior hired keyboards at the IOW – Corea a Hohner Electra piano and Jarrett an RMI electric piano/organ – but both were treated with primitive but strikingly atmospheric effects, including distortion, wah-wah and phase shifter, twisting and contouring the sound into wild new shapes. They were placed on opposite sides of the stage and their probing lines and spacey textures would spin off and collide with each other (monitoring was primitive back then), ramping up the intensity and contrapuntal tension of the music.

Like Tanglewood’s similar set, this 38-minute long uninterrupted piece also took in ‘It’s About That Time’, a short quote from ‘Sanctuary’, ‘Spanish Key’ and then closed out with ‘The Theme’. When asked afterwards what this piece was called, Miles, said: “Call it anything” which became the title of Macero’s 17-minute edit of the performance on the CBS triple LP, The First Great Rock Festivals of the Seventies – Isle of Wight/Atlanta Pop Festival, released in August 1971.

Thankfully the entire weekend was caught on film by director Murray Lerner and a crack team of cameramen. Unlike Woodstock though, the footage didn’t turn into a blockbuster movie. Due to all manner of artistic differences and financial arguments between the organisers, Lerner and lawyers, it took over 25 years to surface as Message to Love, first shown on BBC TV in 1995. It featured a shortish edit of Miles’ set alongside most of the big names, and included backstage and audience footage and commentary, Rikki Farr’s on-stage rants at the fence topplers and a retired IOW naval commander complaining of communist plots and “hippies fucking in the bushes”.

Five years later individual DVD releases started to appear from Eagle Rock containing complete artists’ performances, and in 2004 the full 38-minute Davis set was issued as Miles Electric – A Different Kind Of Blue, which also included recently filmed interviews with all the remaining band members (this DVD was reviewed in Jazzwise Feb 2005). It remains one of the most intense and mesmerising filmed performances from his entire career as he brought his new music to a younger, more diverse audience surfing the wave of the counter-cultural zeitgeist, many of whom, including this writer, would subsequently rush out to buy Bitches Brew and help it become one of the biggest-selling jazz albums of all time.

Murray Lerner’s film not only captures up close the fiery, seat-of-the pants intensity of the performance, but also some of Miles’ most fleetingly intimate and melancholic moments, caught in profile and silhouetted against the falling dusk as his final note is carried off into the cool evening air. He pauses to look at the crowd before slinging his jacket and bag over his shoulder and departing the stage while the band builds to a climatic, drone-like finish. In the deepening shadows behind the amplifier backline he stops for a moment as the crowd erupts into a standing ovation, screaming for an encore. A half-smile plays across his lips as he looks, momentarily, like he might return to the stage to give them more. But he’s Miles Davis, he doesn’t have to.

This article originally appeared in the August 2020 issue of Jazzwise. Never miss an issue – subscribe today!